Missouri Western State University 2006

From 2006.igem.org

(→'''Project Overview''') |

(→'''Project Overview''') |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

<big> <font color="blue">Solving the Pancake Problem with an E. coli Computer </font color> </big><br> | <big> <font color="blue">Solving the Pancake Problem with an E. coli Computer </font color> </big><br> | ||

| - | |||

Our goal is to genetically engineer a biological system that can compute solutions to a puzzle called the burnt pancake problem. The EHOP computer is a proof of concept for computing in vivo, with implications for future data storage devices and transgenic systems. Our work was done in collaboration with the Davidson College iGEM team. | Our goal is to genetically engineer a biological system that can compute solutions to a puzzle called the burnt pancake problem. The EHOP computer is a proof of concept for computing in vivo, with implications for future data storage devices and transgenic systems. Our work was done in collaboration with the Davidson College iGEM team. | ||

<big> <font color="blue">The Burnt Pancake Problem</font color> </big><br> | <big> <font color="blue">The Burnt Pancake Problem</font color> </big><br> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

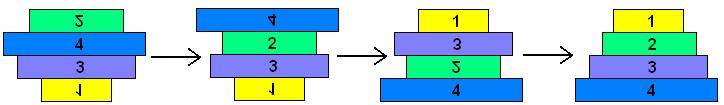

The pancake problem is a puzzle in which a scrambled series of units (or stack of pancakes) must be shuffled into the correct order and orientation. In the burnt pancake problem, each pancake is given an orientation by burning one side. The The leftmost stack in Figure 1 below shows a scrambled stack of burnt pancakes. To solve the problem, every unit, or pancake, must be placed in the proper order (largest on bottom, smallest on top) and in the proper orientation (burnt side down, golden side up). The pancakes are flipped with two spatulas: one to lift pancakes off the top of the stack (if needed), the other to flip part (or all) of the remaining stack of pancakes. The pancakes lifted by the first spatula are returned to the top of the stack without being flipped. The illustration below shows that this stack of pancakes can be put into correct order and orientation in three such steps. One can verify that no two allowable flips are sufficient. Mathematically, one question sorrounding this scenario is to determine the least number of allowable two-spatula flips needed to change a given arrangement of pancakes into the correct order and orientation. | The pancake problem is a puzzle in which a scrambled series of units (or stack of pancakes) must be shuffled into the correct order and orientation. In the burnt pancake problem, each pancake is given an orientation by burning one side. The The leftmost stack in Figure 1 below shows a scrambled stack of burnt pancakes. To solve the problem, every unit, or pancake, must be placed in the proper order (largest on bottom, smallest on top) and in the proper orientation (burnt side down, golden side up). The pancakes are flipped with two spatulas: one to lift pancakes off the top of the stack (if needed), the other to flip part (or all) of the remaining stack of pancakes. The pancakes lifted by the first spatula are returned to the top of the stack without being flipped. The illustration below shows that this stack of pancakes can be put into correct order and orientation in three such steps. One can verify that no two allowable flips are sufficient. Mathematically, one question sorrounding this scenario is to determine the least number of allowable two-spatula flips needed to change a given arrangement of pancakes into the correct order and orientation. | ||

| Line 45: | Line 42: | ||

Figure 1: Illustration of 4-Pancake Burnt Pancake Optimal Solution | Figure 1: Illustration of 4-Pancake Burnt Pancake Optimal Solution | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

<big> <font color="blue">Approach</font color> </big><br> | <big> <font color="blue">Approach</font color> </big><br> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

Trial and error is one approach to solving the burnt pancake problem, but how could one compute the quickest solution? Our idea is to let E. coli do the work, using each cell as a tiny processor in a massively parallel machine. A mathematical model of the flipping process helps us design the system and interpret the output of our EHOP computer. | Trial and error is one approach to solving the burnt pancake problem, but how could one compute the quickest solution? Our idea is to let E. coli do the work, using each cell as a tiny processor in a massively parallel machine. A mathematical model of the flipping process helps us design the system and interpret the output of our EHOP computer. | ||

<big> <font color="red">Biological System</font color> </big><br> | <big> <font color="red">Biological System</font color> </big><br> | ||

| - | |||

The biological representation of a pancake is a functional unit of DNA such as a promoter or coding region. To flip these units of DNA, we have reconstituted the Hin/ Hix invertase system from Salmonella typhimurium as a BioBrick compatible system in E. coli. Hin invertase (BBa_J31001) was cloned from S. typhimurium, Ames strain TA100 and tagged with LVA. We built the recombinational enhancer (RE) and Hin invertase recognition sequence HixC using the publicly available genomic sequence of S. typhimurium and a dsDNA assembly program we created for gene synthesis from overlapping oligos. | The biological representation of a pancake is a functional unit of DNA such as a promoter or coding region. To flip these units of DNA, we have reconstituted the Hin/ Hix invertase system from Salmonella typhimurium as a BioBrick compatible system in E. coli. Hin invertase (BBa_J31001) was cloned from S. typhimurium, Ames strain TA100 and tagged with LVA. We built the recombinational enhancer (RE) and Hin invertase recognition sequence HixC using the publicly available genomic sequence of S. typhimurium and a dsDNA assembly program we created for gene synthesis from overlapping oligos. | ||

| Line 65: | Line 57: | ||

<big> <font color="red">Mathematics</font color> </big><br> | <big> <font color="red">Mathematics</font color> </big><br> | ||

| - | |||

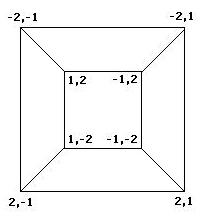

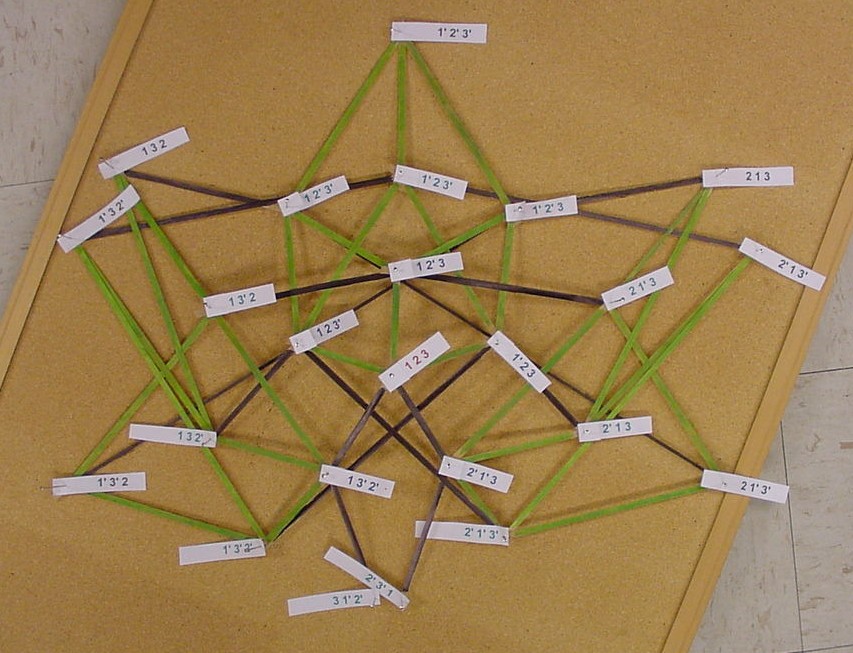

To better understand the possible results of the flipping of biological pancakes, it was necessary to better understand the combinatorial mathematics underlying the process. For a burnt pancake problem involving n pancakes, there are n!2^n possible orders and orientations of the pancakes. A graph representing the relationships between the 8 orders and orientations of two pancakes is given if Figure 3 below. This is useful in understanding "how close" one stack is to another. For example, if a stack begins as -2,1 and ends in the final position of 1,2, then we know AT LEAST two flips took place, although we can not determine exactly which flips or how many. The flipping of a stack from an initial position to the final position corresponds to what is called a walk in the graph. | To better understand the possible results of the flipping of biological pancakes, it was necessary to better understand the combinatorial mathematics underlying the process. For a burnt pancake problem involving n pancakes, there are n!2^n possible orders and orientations of the pancakes. A graph representing the relationships between the 8 orders and orientations of two pancakes is given if Figure 3 below. This is useful in understanding "how close" one stack is to another. For example, if a stack begins as -2,1 and ends in the final position of 1,2, then we know AT LEAST two flips took place, although we can not determine exactly which flips or how many. The flipping of a stack from an initial position to the final position corresponds to what is called a walk in the graph. | ||

| - | [[Image:2-pancakeGraph.jpg| | + | [[Image:2-pancakeGraph.jpg|300px|]] |

Figure 3: Relationships among stacks of two pancakes | Figure 3: Relationships among stacks of two pancakes | ||

| Line 87: | Line 78: | ||

A population of E. coli cells (1015 cells, for instance) each carrying ~100 copies of pancake stacks has astounding parallel processing capacity. | A population of E. coli cells (1015 cells, for instance) each carrying ~100 copies of pancake stacks has astounding parallel processing capacity. | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

<big> <font color="blue">Methods and Results</font color> </big><br> | <big> <font color="blue">Methods and Results</font color> </big><br> | ||

Revision as of 01:49, 29 October 2006

See [http://www.flickr.com/search/?q=igem+missouri photos] from the Ambassador visit on June 5-6, 2006.

Contents |

Students

• Marian L. Broderick, senior mathematics major, [1]

• Adam D. Brown, senior biology major, [2]

• Trevor L. Butner, senior biochemistry/molecular biology major, [3]

• Lane H. Heard, Central High School (St. Joseph) senior, [4]

• Eric L. Jessen, senior biology major (health sciences), [5]

• Kelly J. Malloy, senior biology/chemistry major (health professions), [6]

• Brad J. Ogden, senior biology major (health sciences), [7]

Faculty

• Todd Eckdahl [http://staff.missouriwestern.edu/~eckdahl/], Professor, Department of Biology, [8]

• Jeff Poet [http://staff.missouriwestern.edu/~poet/], Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science, Mathematics, and Physics, [9]

Shipping Address: Todd Eckdahl, Biology Department, Missouri Western State University, 4525 Downs Drive, Saint Joseph, MO, 64507 [(816) 271-5873]

Project Overview

Solving the Pancake Problem with an E. coli Computer

Our goal is to genetically engineer a biological system that can compute solutions to a puzzle called the burnt pancake problem. The EHOP computer is a proof of concept for computing in vivo, with implications for future data storage devices and transgenic systems. Our work was done in collaboration with the Davidson College iGEM team.

The Burnt Pancake Problem

The pancake problem is a puzzle in which a scrambled series of units (or stack of pancakes) must be shuffled into the correct order and orientation. In the burnt pancake problem, each pancake is given an orientation by burning one side. The The leftmost stack in Figure 1 below shows a scrambled stack of burnt pancakes. To solve the problem, every unit, or pancake, must be placed in the proper order (largest on bottom, smallest on top) and in the proper orientation (burnt side down, golden side up). The pancakes are flipped with two spatulas: one to lift pancakes off the top of the stack (if needed), the other to flip part (or all) of the remaining stack of pancakes. The pancakes lifted by the first spatula are returned to the top of the stack without being flipped. The illustration below shows that this stack of pancakes can be put into correct order and orientation in three such steps. One can verify that no two allowable flips are sufficient. Mathematically, one question sorrounding this scenario is to determine the least number of allowable two-spatula flips needed to change a given arrangement of pancakes into the correct order and orientation.

Figure 1: Illustration of 4-Pancake Burnt Pancake Optimal Solution

Approach

Trial and error is one approach to solving the burnt pancake problem, but how could one compute the quickest solution? Our idea is to let E. coli do the work, using each cell as a tiny processor in a massively parallel machine. A mathematical model of the flipping process helps us design the system and interpret the output of our EHOP computer.

Biological System

The biological representation of a pancake is a functional unit of DNA such as a promoter or coding region. To flip these units of DNA, we have reconstituted the Hin/ Hix invertase system from Salmonella typhimurium as a BioBrick compatible system in E. coli. Hin invertase (BBa_J31001) was cloned from S. typhimurium, Ames strain TA100 and tagged with LVA. We built the recombinational enhancer (RE) and Hin invertase recognition sequence HixC using the publicly available genomic sequence of S. typhimurium and a dsDNA assembly program we created for gene synthesis from overlapping oligos.

Every segment of DNA flanked by a pair of HixC sites is a "pancake" capable of being inverted. Hin invertase recognizes pairs of HixC sites and inverts the DNA fragment in between the two HixC sites with the help of the Fis protein bound to the RE. In our system, selectable phenotypes (including antibiotic resistance and RFP expression), depend upon the proper arrangement of a series of HixC-flanked DNA segments in a plasmid. This allows us to select for cells that have successfully solved the puzzle.

Figure 2 A sorted stack of two biological "pancakes"

Mathematics

To better understand the possible results of the flipping of biological pancakes, it was necessary to better understand the combinatorial mathematics underlying the process. For a burnt pancake problem involving n pancakes, there are n!2^n possible orders and orientations of the pancakes. A graph representing the relationships between the 8 orders and orientations of two pancakes is given if Figure 3 below. This is useful in understanding "how close" one stack is to another. For example, if a stack begins as -2,1 and ends in the final position of 1,2, then we know AT LEAST two flips took place, although we can not determine exactly which flips or how many. The flipping of a stack from an initial position to the final position corresponds to what is called a walk in the graph.

Figure 3: Relationships among stacks of two pancakes

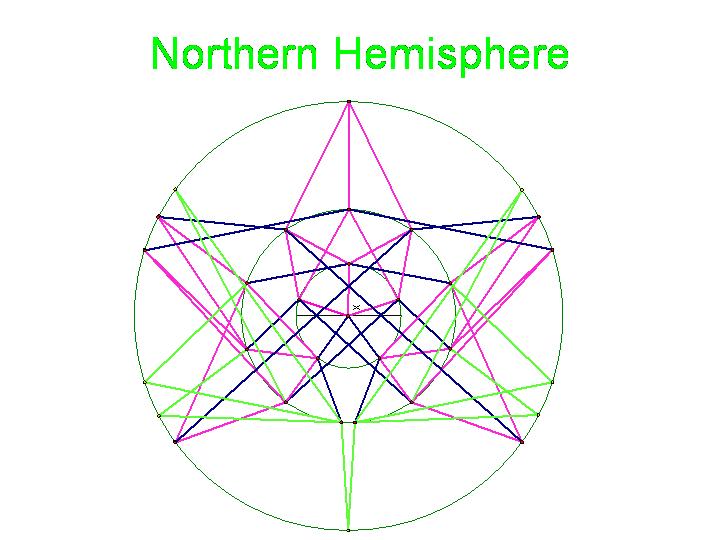

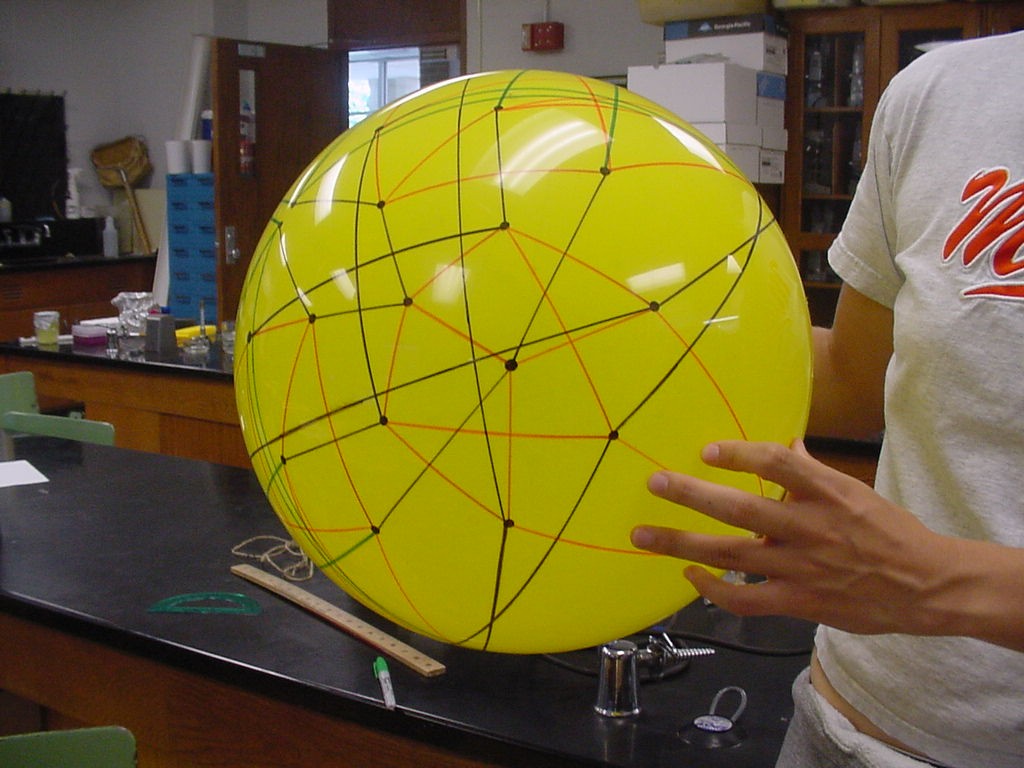

Note that there are 48 possible stacks of three burnt pancakes. While this graph is far more unwieldy, we were able to model this graph on a sphere. Figure 4 below illustrates the view of the sphere from the "North Star". The graph below has one vertex at the North Pole, five vertices on the Arctic Circle, eleven vertices on the Tropic of Capricorn, and fourteen vertices on the Equator. The southern hemisphere is an inversion of this graph. Figure 5 is a picture of the full graph with 48 vertices on a sphere representing the 3-pancake problem.

Figure 4a: Northern Hemisphere

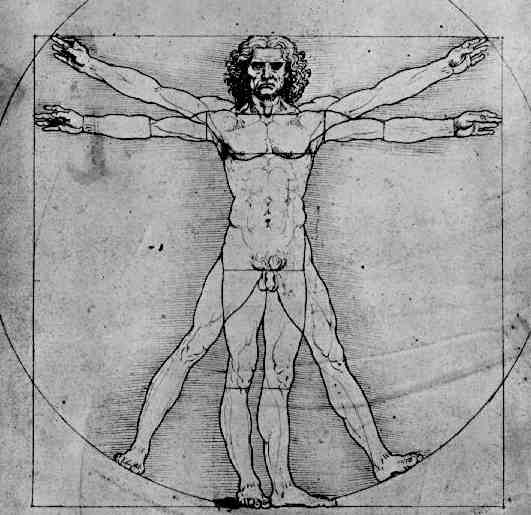

Figure 4b: Anyone else see DaVinci's Vitruvian Man in this, or is it just us?

Figure 5: Full graph of the 3-burnt pancake problem

A population of E. coli cells (1015 cells, for instance) each carrying ~100 copies of pancake stacks has astounding parallel processing capacity.

Methods and Results

Basic parts: Parts used in this project were designed by the Missouri Western and Davidson iGEM teams

http://partsregistry.org/cgi/partsdb/pgroup.cgi?pgroup=iGEM2006partsregistry.org/cgi/partsdb/pgroup.cgi?pgroup=iGEM2006&group=Missouri

Modeling

Modeling the behavior of pancake flipping: deducing kinetics and size biases Using modeling to choose which families of unsolved pancake stacks to start with Building the Biological System

Single pancakes The problems of read-through - uncontrolled Tet expression, uncontrolled flipping New pSB1A7 vector: insulates, but is not compatible with parts carrying double terminators Designing pancakes without TT's

Two pancake constructs Biological equivalence - distinguishing 1,2 from -2,-1 using RFP-RBS, updated panckaes

Conclusions

Consequences of devices: data storage, possible application for rearranging transgenes in vivo, proof-of-concept for bacterial computers, first in vivo controlled flipping of DNA??

Next steps: can solve problem but need control over kinetics

Lessons learned:

Troubleshooting, communication, teamwork, publicity

Math and Biology meshed really well and even uncovered a new proof

Multiple campuses can increase capacity through communication and cooperation

Size of school is not a limiting factor

We had a blast and learned heaps

Retrieved from "http://partsregistry.org/cgi/partsdb/pgroup.cgi?pgroup=iGEM2006partsregistry.org/cgi/partsdb/pgroup.cgi?pgroup=iGEM2006&group=Missouri"

Assembly Plan

Math Stuff

The picture below is of the half graph for the signed permutations for the 3-pancake problem. The full graph would have 48 vertices with each connected to six other vertices. The plan is to transfer this half graph onto the northern hemisphere of a globe with 123 as the north pole, five permutations on the Arctic Circle, eleven on the Tropic of Capricorn, and seven on the equator. An identical graph can be placed on the southern hemisphere such that each permutation occurs diametrically opposite its biological complement. In the picture below, green edges correspond to flips involving one pancake only and black edges correspond to a flip in which a double pancake is involved.

The graphic below was created using Geometer's SketchPad by Marian and shows the 24 vertices on the Northern Hemisphere, similar to the pushpin and rubber band manipulative above. The edges in this graph represent the relationships among the permutations. Pink edges correspond to the flip of a single pancake, black edges to the flip of a double, and green edges to vertices in the Southern Hemisphere. A 3-D model on a globe (okay, it is really a beachball) is in progress. Of curious note, doesn't this graph look similar to Da Vinci's Vitruvian Man?

This image is the connected graph of forty-eight vertices on a sphere....finally!

Publicity

MWSU Tower Topics [http://staff.missouriwestern.edu/~eckdahl/iGEM/Tower_Topics_7_2006.htm]

St. Joseph News-Press [http://staff.missouriwestern.edu/~eckdahl/iGEM/St_Joseph_NewsPress_7_2006.htm]

Research Links

OWW Protocols [http://openwetware.org/wiki/Protocols]

Source Plates [http://2006.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Biobrick_delivery&printable=yes]

Goodman et al. 1973-1979. The Pancake Problems [http://www.math.uiuc.edu/~west/openp/pancake.html]

Nanassy and Hughes. 1998. In Vivo Identification of Intermediate Stages of the DNA Inversion Reaction Catlyzed by the Salmonella Hin Recombinase [http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/abstract/149/4/1649]

Lim et al. 1997. Hin-mediated Inversion on Positively Supercoiled DNA [http://www.jbc.org/cgi/content/full/272/29/18434]

Hughes et al. 1992. Sequence-specific interaction of the Salmonella Hin recombinase in both major and minor grooves of DNA [http://www.pubmedcentral.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=1628628]

Nanassy and Hughes. 2001. Hin Recombinase Mutants Functionally Disrupted in Interactions with Fis [http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/full/183/1/28?view=long&pmid=11114897]

Lee et al. 1998. In Vivo Assay of Protein-Protein Interactions in Hin-Mediated DNA Inversion [http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/180/22/5954]

Merickel et al. 1998. Communication between Hin recombinase and Fis regulatory subunits during coordinate activation of Hin-catalyzed site-specific DNA inversion [http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/content/abstract/12/17/2803]

Haykinson and Johnson. 1993. DNA looping and the helical repeat in vitro and in vivo: effect of HU protein and enhancer location on Hin invertasome assembly [http://www.pubmedcentral.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=8508775]

Vasquez et al. 2004. Tangle Analysis of Gin Site-specific Recombination [http://math.berkeley.edu/~mariel/Vazquez_Gin04.pdf]

Merickel and Johnson. 2004. Topological analysis of Hin-catalysed DNA recombination in vivo and in vitro [http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03890.x]

R.C. Johnson and M.F. Bruist. 1989. Intermediates in Hin-mediated DNA inversion: a role for Fis and the recombinational enhancer in the strand exchange reaction [http://www.pubmedcentral.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&blobtype=pdf&artid=400990]

Lim and Simon. 1992. The Role of Negative Supercoiling in Hin-mediated Site-Specific Recombination[http://www.jbc.org/cgi/content/abstract/267/16/11176]

The Pancake Tossing World Record[http://www.recordholders.org/en/records/pancake.html]

Cool site for Breakfast [http://www.cut-the-knot.org/SimpleGames/Flipper.shtml]

iGEM iDeas

Powerpoint with two possible project ideas. [http://staff.missouriwestern.edu/~eckdahl/Research/Synthetic_Biology_2006/IGEMideas%2005-29-06.ppt]

Protocols

To Do List

Since I have severe separation anxiety, post what you did and how things turned out each day right here. Then I can offer suggestions and help plan the next steps.

Monday

Plasmid Prep

Vector Digestions

Develop Assembly Schedule

Tuesday

Trevor: We will have to make reversed RBS and reversed double terminator - design PCR primers for this the way we did for the reversed pAra on Friday and post the proposed sequences here.

cloning hix fragments

Wednesday

Making Reverse pARA

Thursday

Oligos should arrive for reverse RBS and TT (described on Assembly page). Do Reverse Parts with PCR

Pick four colonies off each of the transformation plates (except vector only plates) from yesterday and put into 5 ml LB+Amp at 37C overnight for plasmid preps tomorrow.

Friday

Do plasmid preps on overnight cultures

Measure plasmid yields with UV spec

Digest 200 ng (if that is not most of what we have) of plasmids with XbaI + SpeI and run on 12% PA

Start overnight cultures from transformations done on Thursday

Below are some questions from Jeff and some responses by Todd:

1. Can we double up on some constructions like Promoter(Forward) and Promoter(Reverse) by inserting them into a plasmid that already has a Hix site and getting a 50-50 split (which we can presumably separate out)?

I think it would be better to keep the two promoter orientations as separate constructions.

2. Could we start with a plasmid with a Hix site and insert several things at the same time and then sort them out later? (Example: could we put in a short promoter, a medium length RBS, and a long coding region at the same time and sort them out by length as to which connected? I think this is what you referred to as shotgun ligation when we were discussing the Traveling Salesman Problem.)

Again, I think that keeping things separate will be easier in the long run.

3. Should Hix be the LAST thing in any subconstruction so that we can create a version with HixL, one with HixR, and one with Hix C?

I guess this boils down to the question of how big of a library of parts do we want to create. Is it the case that every time we want to have a Hix site, we need one of each type of Hix? If we take this approach, then we can investigate any differences between the types of Hix sites, perhaps finding the most effective/efficient combination.

The way I see it, there will be four pancakes, each in two orientations, and each one will have a hixC on the right (3') end. That way, each could be used in modular fashion to make any of the four pancake constructs we want.

I think that for now we should head for the construction of parts that can be used in the two different one-pancake devices that will work in the four-pancake ones. I think we should concentrate for now on using hixC only. The problem can be subdivided into the following three devices: Hin recombinase producer, pancake flipping operon, and recombination enhancer.

Davidson Team: We believe we have Hix L, R and C cloned. We need to sequence these to verify. Also, we believe we have RE cloned. Again, we need to sequence this. We are still waiting for PCR primers for Hin. We will tackle this as soon as a pair shows up.

Davidson Team: We like Todd's idea of a part + HixC on the 3' end. The most efficient way to produce this is to use a plasmid with Hix already in it. Do NOT try to cut out a Hix and then clone it. It is too small (26 bp). So always clone the bigger piece into the HixC vector. However, for one pancake devices, we'll need to have Hix on bothsides of Promoter and none on the RBS+coding followed by a separate Terminator.

Davidson Team: We are working on the visuals and will add them to our wiki soon.

From Todd: Great work, Davidson Team! We need to continue to plan our assembly and divide and conquer. Jeff and our students are working on a schedule for assembly and there are also some thoughts at Develop Assembly Schedule. We are working on making reversed pAra this week and will also make plans to make reverse RBS and TT, which we will need eventually.